GARS had the honour of fighting in the Staatsen army in de Slag om Grolle, the greatest European 17th century event, last October. There were no Finnish troops present at the historical Siege of Grolle of 1627, but in fact Finnish soldiers did take part in the Dutch-Spanish war six years later. In the late summer of 1633 the Dutch paid for Swedish cavalry to join Frederick Henry’s invasion of Brabant. The force of around 1000 Swedes and 650 Finns was led by legendary commander of Finnish ”Hakkapeliitta” cavalry: Torsten Stålhandske. Colonel Stålhandske had just been wounded in the siege of Hameln but apparently not very seriously: he, like many other famous commanders of the time, was rumoured to have been bulletproof by magical means.

Born in Borgå, Finland, Torsten Stålhandske had Swedish father, Finnish mother and was raised by Scottish stepfather. He was friends with several Scottish officers in Gustavus Adolphus’s army and because of that his deeds are well covered in William Watt’s “The Swedish Intelligencer”, where is noted that Stålhandske ”speakes excellent good english”.

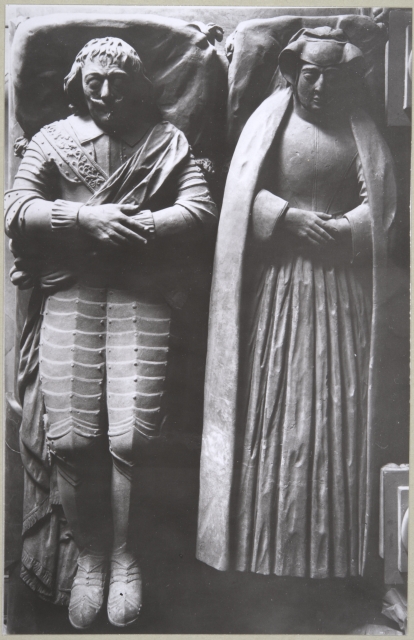

Photo: Tomb effigies of Torsten Stålhandske and Christina Horn in Turku Cathedral, Finna.

Mustered in 22th of August, the Swedish force was paired up with 3000-strong contingent of Hessian horse, and when Hessian commander Dalwig resigned Stålhandske was put to the head of the whole force and appointed as Hessian generalmajor: a bit later he received the same rank also in Swedish army, so the Dutch adventure did benefit Stålhandske’s career development. It did less impact militarily: the enemy commander, Marquis of Aytona, avoided confrontation so apart from a couple skirmishes in September there was very little action or effect. For the latter part of their service, Stålhandske’s force was sent to set up a camp on the Maas river.

There were also problems with payment, so parts of the cavalry force resorted to looting. The Hessians especially were quick to start terrorizing the peasantry (the Dutch complained that they only had joined the fight because they’d already eaten everything in Westphalia) but a bit later, while stationed in Liege, also the Stalhåndske’s own men did their share. Dutch reports from the beginning of October speak of ”…met rouven ende plunderen van adelijk huijsen ende geheele dorpen”. From the casualty lists we know that also Finns did fight with the civilians and one trooper was sentenced to death, probably for pillaging.

Prince of Orange Frederick Henry, stadtholder of Netherlands. His first impressions of the Stålhandske’s men’s equipment were not so terrific: ”…de Septembre Stalhans arriva avec cinq cents chevaux aucunement bons hommes mais mal armés & montés.” Memoires de Frederic Henri Prince d’Orange

Soon after the clashes with civilians of Liege the Swedish-Finnish cavalry was released from Dutch service and sent back across the Rhine. The Dutch paid Swedish crown 600 000 guldens for the short (under two months) and quite irrelevant service of Stålhandske’s men: a huge sum, twice the size of annual subsidiary Sweden received from the France. It was not a particularly hard campaign for the Finns: casualty lists mention four cavalry troopers fallen in the Netherlands: Simo Karppi, Lasse Mortensson, Mats Grelsson, and Matts Mattson. And then Eskil Hendrichson was murdered by peasants and Jaakko Larsson was executed.

More on the subject:

Detlev Pleiss: Der Zug der finnischen Reiter in die Niederlande via Wesel 1633 (1998)

Sebastian Jägerhorn: Hårdast bland de hårda : en kavalleriofficer i fält (2018)